Abstract: For a long time, companies have been unaware of or unconcerned with their activities’ consequences to the environment. In the 1990s, however, this narrow-minded attitude seemed to begin changing, as some signs increasingly appeared: overcompliance with regulation standards, voluntary environmental expenditures and agreements with regulators, the appearance of “green” products, corporate statements on the environment and implementation of environmental management systems, among others. If companies are now taking the environment into account, they probably have an economic pull for doing so. The interaction process with regulators, stakeholders’ pressure, corporate reputation enhancement, creation and taking advantage of competitive opportunities, and the view of corporate environmentalism as a strategic issue are the reasons examined here in order to evaluate the potential benefits for environmental integration in companies’ management orientation. This article tries to present corporate environmental strategic management as an essential management function because of its ability to minimize costs and risks and enhance companies’ value.

1 Introduction

The environment has always been undoubtedly interconnected with the corporate or business field. Particularly in the industrial and agriculture sectors, it has always had a major weight. This important relationship had already been recognised by the classical economists from the 18th and 19th centuries. According to them, no economic activity could be carried out in the absence of the three economic factors: labour, capital and land. For the most prominent classical economists, natural resources were the central basis of the law of diminishing returns, which in turn would lead the economy into a stationary state. However, neoclassical theory has condensed the economic factors into two – labour and capital. Even so, the environment was always coupled with the economic activity, at least in the form of raw materials and energy required for production processes and, ultimately, for handling waste products.

Until the 1960s, this was the generally considered relationship between environment and economic activity: industries incorporated it into consumer products, in the form of raw materials and energy, without being aware of their activities’ possible impacts on the future availability of natural resources and on the natural environment’s quality. This myopic perspective resulted in the loss of resources, in the decrease in their quality, and in pollution – endangering global climate conditions, air quality in a number of cities and the survival of several living species.

Numerous events, such as oil spills, acid rain, nuclear accidents and the depletion of the ozone shield, helped the international community and public opinion, at least in the so-called developed world, to become conscious of the consequences of environmental degradation. Also, some public events, like the Earth Summit and the presentation of the Club of Rome’s report, The Limits of Growth, in the 1970s, the publication of the United Nations report, Our Common Future, in the following decade, and Rio’s International Conference at the beginning of the 1990s, played a major role in promoting eco-awareness. A growing number of phenomena have signaled the differences in attitude. International environmental agreements, the government’s environmental policies and regulations, corporate environmental policies and reports, the increasing public power of environmental Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs) and green consumers are just a few of those signs.

Multinational companies, probably owing to their high public exposure, were the first ones to understand the threats of this new context of high public consciousness towards environmental problems and to perceive the need for a good ecological reputation to keep their market share on a global level.

At the same time, the academic world has also given particular attention to this field of study and, especially since the last decade, to the integration of environmental concerns into the corporate and management field. Even some management gurus have been writing about this new management field, and some academic and management journals and reviews on environmental management have appeared.

The debate has been intense between those who advocate that the environment is usually a synonym for non-productive investment, with consequences such as the loss of competitiveness, and those who, on the other hand, believe that the environment can become profitable and can become an important issue in keeping, or even improving, companies’ competitive positions, at least in the medium or long run.

This paper tries to give an image of the state of the art in corporate environmental management and strategy, along with a critical overview of companies’ major drives and conduct towards the environment over the years and an analysis of the principal theoretical positions defended by scholars on this matter.

2 Companies’ perceptions about the environment

For a long time, companies have been unaware of and unconcerned with their activities’ consequences to the environment. Therefore, environmental considerations were never considered in their decision-making process. “Mother Earth” was seen only as a locus and an input source.

When environmental concerns arose at a public level, environmental regulators, with the aim of reducing the impacts of industrial activities on the natural environment, began to impose some rules on a wide range of industry sectors, usually through the definition of maximum pollution standards and the requirement of the undertaking of the best pollution abatement technologies available. For companies, this generally meant the adoption of “end-of-pipe technologies”, which, instead of providing an opportunity for the re-analysis of the entire production process, only reduced the quantity of polluting materials released by the companies. Owing to the high cost of these investments, and to the unpredictability of regulatory demands, environmental regulatory compliance usually corresponded to a big burden on companies’ financial position and to competitive loss against companies from unregulated areas. Consequently, companies began to incorporate the environment in the decision-making processes as the cost of meeting regulatory pollution standards. The later introduction of “market instruments” in the regulatory process did not change industry’s perception of the environment: it was an undesirable cost and a potential threat to the organization’s purposes.

The increase in the complexity of the regulatory phenomenon, together with the additional costs, also led to changes in companies’ internal structure– the creation of an Environmental Health and Security (EH&S) department, particularly in big firms, with the defined purpose of dealing with regulation requirements. Yet this department was seen as being apart from the rest of a company’s structure, and it continues to be so indeed in numerous companies, since this issue meant sunk “cost of doing business”. This separation between EH&S functions and core business ones has been called the “Green Wall”, and it refers to a barrier in translating environmental initiatives into projects that could show business value to upper management”. Being more technological than business oriented, many EH&S executives have not started to understand and communicate internally, in a proper way, the real opportunities that the environment can mean to enterprises. This has been one of the main factors in companies’ delay in achieving a more environment-oriented business management.

3 Signs of change

In the 1990s, though, this narrow attitude regarding environmental considerations seemed to change. Some signs became recurrent in the business field: a growing number of enterprises and industries over complied with environmental regulations, spent high amounts of voluntary environmental expenditures, and abundant voluntary agreements between firms and regulators were set; green products began to be presented in store racks, filling a new niche segment – green consumers; “green marketing” was suddenly a new expression on managers’ and marketers’ lips; big and multinational enterprises implemented environmental policies and voluntarily communicated them to stakeholders through environmental reports and other communication tools; environmental management systems, such as EMAS and ISO 14000, were internationally set and quickly adopted and accepted at a global level; in some companies, environmental considerations even reached the strategic management field.

The question now is – why? Why are companies over complying? Why are companies

adopting “green practices”? What are their motivations? Why should firms integrate environmental management into business functions?

4 Why?

“Companies are not in business to do environmental work. Companies exist to satisfy customers and stakeholders by making money. Any environmental strategy has to be based on understanding how the environment program fits in with the business of the business."

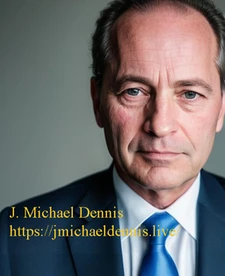

J. Michael Dennis, ll.l., ll.m.

Today, for companies to take the environment into account, they must have an economic pull to do it. Only in the case of prospective benefits, or cost avoidance, would it be rational for companies to incorporate the environment into the business field. Consequently, this issue can also be evaluated in a cost-benefit analysis. Nevertheless, it must be said that a correct application of this framework needs a real, wide and complete definition of all costs involved.

4.1 Regulation

First of all, let’s have a brief overview of the possible motivations behind the corporate decision in complying with environmental regulation. For the regulation to be effective, the expected value of a fine for non-compliance must exceed the cost of compliance. The threat of criminal prosecutions also cannot be forgotten when evaluating corporate or management’s incentives to comply. These reasons support some people’s perspective of the environment as a cost and as a burden.

In spite of that, many companies have registered over compliant positions. When it does not imply a profit loss, at least in the long run, the situation is not difficult enough to justify in economic rational terms. On the other hand, when it means a profit loss, the justification of corporate incentives to over comply seems to be more difficult to find. As far as I am concerned, I classify the explanations into four categories:

- Anticipatory compliance – during the regulatory process, in the interaction between regulator and regulated firm, companies can try to control the kind of future regulations and, by over complying, try to avoid future regulations.

- Creation of barriers to entrance in the market – in their battle to avoid competition and keep high market shares, companies overcompliance can pressure regulators to raise the regulatory standards, lifting the barriers to market entry.

- Indivisibilities in pollution abatement costs – owing to the high costs of pollution abatement technologies and their discontinuity characteristic, companies can choose technologies which reduce their emissions below regulatory standards.

- Pure commitment motive – one of the management goals, indeed, can be the improvement of the natural environment.

4.2 Stakeholders’ pressure

Another reason for integrating environmental concerns in business functions is the increasing pressure from various stakeholders’ groups to do so. Management literature usually identifies the following kinds of stakeholder groups: owners/shareholders, employees, customers, suppliers and the community at large. Each one of these groups has specific expectations about companies’ goals. Companies’ top management must be sensitive to all of them. If their expectations are not met, shareholders may change their investment portfolio and sell their stocks; employees – particularly highly valued human capital– can quit their jobs; unsatisfied customers may switch to companies’ competitors; and suppliers can find other buyers. For our purposes, we use a broader stakeholder definition, which may include, among others, shareholders, employees, customers and consumer groups, regulatory agencies, local communities, NGOs, the media, the general public, suppliers and competitors. Hence, with this definition, the interests of all corporate legitimate stakeholders must be considered in the decision-making process of the firms, and not only shareholders’ expectations.

It has often been pointed out that shareholders are not quite interested in environmental performance but, instead, in companies’ financial and economic performance, signaled by profits, dividends and share prices. Being true, this statement would show investors’ narrow perception of the possible environmental impacts on a company’s value. In fact, weak environmental performance can mean a large number of fines, in those cases in which the industry is regulated; or, in the cases in which they are not, it may attract regulators’ attention. Even without claiming a positive relationship between environmental and financial performances, shareholders must realise that a good environmental performance prevents companies, at the least, from paying expensive fines, clean-up investments and court expenses. Thus, the increasing investors’ concern with socially responsible investment is not strange. In reality, environmental performance enhancement might be considered to be a signal of healthy economic performance in the future.

Customers, who ultimately are the basis of business activity, play a major role in a company’s adoption of environment-friendly practices. With the increase in the education level and the mass-media globalization, customers are becoming more aware of the real impacts of companies’ activities during their processes, from input acquisition to product disposal after use. In fact, many have begun to differentiate companies regarding their environmental and social practices and to take these practices into account in the acquisition process. The green consumers phenomenon is a good indicator of this new threat and, at the same time, a new opportunity for companies.

Environmental NGOs also play a significant role as stakeholders. Undeniably, they are major users of corporate environmental data and information and are important opinion-makers. They warn consumers and their international campaigns mobilize customers and organizations’ attention towards companies’ environmental behaviours. Their actions can have positive or negative effects on firms’ image. Some examples have come into sight about partnerships between companies and environmental NGOs, which resulted in the achievement of an enhanced corporate credibility and in environmental gains.

4.3 Corporate reputation

In this context of global information technologies, any event can be quickly broadcasted to the entire world. Hence, any negative impact on the natural environment caused by companies’ activities can be largely transmitted on a global scale, amplifying by consequence the costs for companies’ image. It is my belief that corporate reputation, acting as a differentiating factor, will be a major determinative in firms’ competitive position. Corporate reputation can be analyzed as an intangible asset, and certainly a very important one, as it is hard for competitors to imitate. Some authors, based on empirical research, even demonstrate. Through the creation of goodwill, the environmental reputation-creation process can be described as a three-stage process. In the first stage, companies must delineate and put into action environmental policies, according to their strategic goals, with the aim of creating competitive advantage and taking stakeholders’ expectations into account. Then, in the second stage, as there is no complete information, companies must disclose their environmental strategy and features to stakeholders, choosing the appropriate signals and channels. And last, in the third stage, reputation is the outcome of the process.

A stronger reputation can leverage financial performance and help firms in accessing the capital market, in enhancing brand image, in increasing customers’ loyalty – as many consumers and business customers often seek to align themselves with firms that have a reputation for social responsibility – in enhancing companies’ attractiveness to employees and in having a more favorable treatment by regulators.

4.4 Competitive opportunities

Extensive literature and econometric studies have questioned the connection between environmental and economic performance. Even without a universal end result, one major conclusion can be taken: they are not mutually exclusive. The prevailing view, which states a trade-off between environment and economy, is inaccurate, as it is based on a static vision that does not take innovation into account. Yet it is now increasingly accepted that firms’ competitiveness stands on lower costs and superior value products, through differentiation. With this new competition paradigm, companies are forced to find new solutions to their problems and pressures. That is why environment integration into business functions can give a wide range of benefits to companies; namely, efficiency enhancement, market share increase, product quality improvement and innovation pressures.

Cost reduction strategies are always consistent with firms’ strategic goals, whatever they are. Through cost reductions, companies can enhance efficiency and improve operational and financial performances. Environmental management and awareness usually offer good opportunities for processes’ revaluation and reengineering, which can lead to new technologies that can minimize the costs of reaching a certain amount of pollution, improve resource productivity – through a more efficient use of inputs and replacement of costly materials – and achieve higher production yields. In addition, this process changes can still improve products’ quality and, therefore, more valuable goods will be offered to consumers.

In practice, management must identify all resources integrated in a company’s value chain and try to find underutilized resources, process inefficiencies and avoidable packaging. In this process evaluation, life cycle analysis is a good tool, since it allows a wide and even complete vision of companies’ impacts, beginning with raw materials acquisition and ending with final product disposal. An integral perception of the entire cycle allows engineers and industrial designers to reevaluate product materials, design and packaging. In doing so, companies will be able to recognise cost reduction opportunities more easily. Energy conservation, materials recycling and waste minimization are excellent examples of cost minimization procedures with a double dividend – they are environment friendly and enhance firms’ efficiency. These unexploited cost minimization procedures show that enterprises have been registering higher costs than they could be doing, a phenomenon known in the economic literature as “X-inefficiency”. In reality, profit maximization does not always mean cost minimization. But not only cost reduction can enhance companies’ efficiency. Firm pollution can be understood as a kind of economic waste, as a sign that resources have been used incompletely, inefficiently, or ineffectively or not used to generate their highest value. Thereby, environmental problems become economic and management problems and, consequently, they deserve special attention.

Consumers are becoming more concerned about environmental questions and are beginning to differentiate firms through their perception of companies’ environmental performance. Accordingly, they are increasingly demanding green products, which present low levels of pollution and are energy efficient. Despite not usually being specified as a major driver of environment integration, “green consumerism’s” potential for the opening of new market segments for new product development and for charging green price premiums cannot be dismissed by company departments, from R&D to marketing.

4.5 Strategic issue: corporate environmentalism

More and more, corporate environmental management is considered an essential management function for its ability to minimize costs and risks and enhance companies’ value – a great number of examples can be given of environmental concern’s embrace at every level of companies’ strategy and corporate mission. In the aim to achieve a competitive advantage in their markets, corporate strategy defines a firm’s role in society, a company’s presence in several markets and business, technology development and use, and its own organizational structure. In all of these tasks, environmental concerns must play a key role as an ethical, operational or competitive view, just as companies’ characteristics and external conditions ought to.

Environmental strategic attitude is frequently characterized as reactive or proactive, concerning firms’ actions in the competitive scenario and the main drivers of environmental behaviour. A reactive strategy incorporates environmental concerns as a way of avoiding their negative impacts. By responding to environmental regulation or to stakeholder and market pressures, companies who choose this strategy wish to keep neutral to environmental changes. Proactive strategies, on the other hand, realizing the opportunities opened up by environmental management, aim to achieve a better corporate competitive position through their use as a support for the entire business strategy. Companies following proactive strategies try to anticipate market and environmental context evolutions, introducing new products and adopting new production technologies. Unlike proactive strategies, reactive ones can neither create nor sustain a competitive advantage.

“Corporate environmentalism is the organization-wide recognition of the legitimacy and importance of the environment in the formulation of organizations’ strategy, and the integration of environmental issues into the strategic planning process.”

J. Michael Dennis ll.l., ll.m.

The environment can be integrated at different levels in an organisation: enterprise, corporate, business and functional. ‘Nevertheless, to be effective, the environment’s integration requires the involvement of the entire organisation. First, environmental management must be recognised as a priority. Top management thus plays a major role, since the entire company must recognise their support and commitment. All employees must be aware of environmental issues, and workforce performance evaluation may also include environmental considerations. Goal formulation is, therefore, a necessary step if environmental performance is to be appraised and, hence, plays a key role in a company’s strategy. Finally, for further integration, environmental considerations must incorporate all of a company’s functions. This will improve evaluation and decision-making systems; and so, environmental achievements will naturally occur.

5 Conclusion: is an environmental mode of business really needed?

“Being green” is fashionable, chic, and a social and politically correct thing to assert nowadays. Nonetheless, the mere generative concern of companies’ owners and managers for the future, particularly for Planet Earth and the coming generations’ future, was not as great as was necessary to make them conscious about environmental problems and, consequently, to force them to act in an environment-friendly way, especially because it was assumed that environmental actions have a downside: a substantial profit loss. Indeed, a fixed trade-off between environmental actions and economic performance has been proclaimed for a long time, and to be honest, it still is by many economists and company managers. Unfortunately, the consequences of this myopic standpoint are not very pleasant for “Mother Earth’.

For most of us living in the Western industrialized world, unfortunately, we live “in the moment and for the moment”. So, in such a complex field like the environment, where a broad number of strange relations and interrelations between the biophysical world and living beings coexist, it may not be complicated or erroneous to declare that the long-term and two-sided connections between economy and environment have not yet been clearly understood. As far as I am concerned, I believe that, in the context of the prevailing competition paradigm, there are quite a number of valuable reasons and much evidence to consider that the stated trade-off is no longer valid.

In the last decades, managers have learned that they need to meet the various stakeholder groups’ expectations and respond to their pressures in an effective and contemporary way. For investors, environmental performance analysis and data will continue to be increasingly vital, as they need to be fully aware of companies’ risks, liabilities, costs and available opportunities for a correct investment valuation. For the older generation of investors, these links may not be easy to perceive; however, it is our firm belief that the new generation will be more capable of doing this. Customers, more and more influenced by the media and NGO campaigns, keep the key role in companies’ strategy formulation. They will intensify their demand for green products and companies’ responsible and proactive social, ethical and environmental behaviour. Corporate governance and actions that augment corporate reputation can also play an important task in improving relations with stakeholders and consequently assuring competitive advantages.

Apart from meeting stakeholder expectations, there are other reasons for the absence of an absolute trade-off. As a matter of fact, it is possible to convert environmental investments into profitable ones. Environmental pressures may offer great opportunities for innovating and for process and product revaluation. In the course of their processes and product life cycle analysis, companies can perceive inefficiencies in environmental and operational performance. By amending them, through actions such as waste and energy minimization, removing unnecessary production stages, and product redesigning, companies can enhance their efficiency and thus offset environmental costs. Moreover, this redoubled attention to environmental issues can give some tips for new product and market development and for the “creation” of new consumer needs, tempting customers’ environment-friendly psyche.

Finally, in playing a proactive role in integrating environmental concerns into business strategy, decision-making systems and performance evaluation, companies will gain a renewed framework that, through learning, will enable them to compete in the ferocious global markets of this new millennium.

As every new issue in any science, environmental management will take time to be incorporated in the mainstream. Meanwhile, extensive research is still needed to strengthen this new way of doing business and to give it the effective tools that are still missing. Yet, in my opinion, global environmental goals will be met more quickly and in a better manner if they are integrated on a business perspective level, rather than solely by government or intergovernmental solutions, as has been tried. Certainly, well-defined cooperation between the business world and governments, and not only through the regulatory process, would achieve quicker and better solutions, probably the “win-win” type ones – a double dividend for the environment and for the economy and our well-being.

J. Michael Dennis

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Michel Ouellette JMD ll.l., ll.m.

Michel Ouellette, also known as J. Michael Dennis, is a graduate of the University of Ottawa, where he specialized in Commercial and Business Law. His focus areas included “Institutional Regulatory Compliance”, “Corporate and Public Officers' Liability”, “Collective Agreement Negotiations”, and “The Impact of Corporate Fiscal Legislation on Business Decision-Making”.

Following the Bhopal disaster of December 2-3, 1984, involving Union Carbide, and after a decade serving as the National Canadian SCMS Coordinator for Union Carbide Corporation, J. Michael Dennis transitioned to specialize in “Public Affairs” and “Corporate Communications”. His consulting expertise spans “Personal and Organizational Planning”, “Change and Knowledge Management”, “Operational Issues”, “Conflict Resolution”, “Regulatory Compliance”, “Strategic Planning”, and “Crisis and Reputation Management”.

Today, J. Michael Dennis focuses on emerging trends and developments that are shaping how we live and conduct business. As an expert in Regulatory Compliance, Strategic Planning, and Crisis, Reputation Management, J. Michael Dennis provides valuable insights on the years to come to business owners, corporate officers, managers, and the public. His exhaustive analysis covers a broad spectrum of future trends, technological advancements, lifestyle changes, and global issues that will impact the way we live and do business in the years ahead.

Contact J. Michael Dennis

Web: https://www.jmichaeldennis.live/

eMail: jmdlive@jmichaeldennis.live

Skype: jmdlive